Something very significant happened 156 years ago today. Not

even six weeks into his presidency, Abraham Lincoln was informed that the U.S.

Fort Sumter in Charleston Bay had been bombarded and had fallen to a South

Carolina militia led by General P.G.T. Beauregard. The Civil War had begun and Lincoln’s leadership

was put on alert and tested at every turn of events during the next four years.

His handling of this crisis defined his presidency and became a model of

leadership for every generation since then.

Something very significant happened 156 years ago today. Not

even six weeks into his presidency, Abraham Lincoln was informed that the U.S.

Fort Sumter in Charleston Bay had been bombarded and had fallen to a South

Carolina militia led by General P.G.T. Beauregard. The Civil War had begun and Lincoln’s leadership

was put on alert and tested at every turn of events during the next four years.

His handling of this crisis defined his presidency and became a model of

leadership for every generation since then.

Lincoln

was not unfamiliar with adversity. Before he was ever elected in 1860, several

southern states had made overtures about secession if he became president.

Shortly after he won the election, South Carolina made good on this threat and

withdrew from the United States on December 20, 1860. When Lincoln was sworn in

at his first inauguration, a total of seven states had seceded from the Union. Since

then, he had worked to turn the tide on secession diplomatically, even going so

far as to ask permission of South Carolina to have Union troops resupply Fort

Sumter with food in early April. Instead, the fort was bombarded starting on

April 12. The attack on Fort Sumter changed things. The day after the fort was

surrendered, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to go to war. This was met

with enthusiasm in the north and derision in the south. Soon after, four more

states: Arkansas, Tennessee, Virginia and North Carolina seceded and formed

state militias to fight for the South. It looked like every move that Lincoln

made just caused the situation to worsen. In the midst of it, Lincoln steeled

his resolve to fight for the reunification of the states and to put an end to

the issue that divided them: slavery.

I

like strong leaders. I am drawn to people who have stood upon their values and

fought for what they believed was right. It has been said that adversity

doesn’t build character, it reveals it.1 But when you are in the

midst of a conflict, how do you know when to stand and when to sit down? Take a

lesson from Abraham Lincoln in the midst of the Civil War.

Lincoln simplified a complex

issue

The

slavery debate had been going on since the beginning of the country. Founding

fathers, such as Benjamin Franklin, Samuel Adams, and John Adams opposed

slavery. They thought it was immoral. Southern plantation owners, such as

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, were slave owners. They saw it as an

economic necessity. The Constitution was ratified partially because it avoided

the slavery issue. As the nation grew, pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions

clashed in Congress, in the courtroom, in churches and on the state borders. In

his political campaigns, Lincoln had called the slavery issue a "House

Divided.” In his mind, it had to be resolved. The nation could not go on living

as half free and half slave. "I believe this government cannot

endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be

dissolved—I do not expect the house

to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.”2

Lincoln

leadership principle #1: If you want to solve a problem, you have to define it

so that there is no gray area. You are either one thing, or you are the other.

You cannot be both.

Lincoln stood resolved on one

point that everyone could believe in

Lincoln

despised slavery, but he knew if he made slavery the central issue of the war,

he would lose the support of some of his constituents. The north had a very

strong abolitionist movement that had helped him get elected, but in war, he

needed the support of those that were pro-slavery or neutral on the slavery

issue to get behind the war effort. He made the preservation of the Union his

main reason for continuing the fight until the war was won. Here is the last

sentence of his Gettysburg Address:

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task

remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to

that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here

highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation,

under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people,

by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.3

Lincoln

leadership principle #2: Find common ground on which those following you can

agree.

Find leaders who believe in

your vision

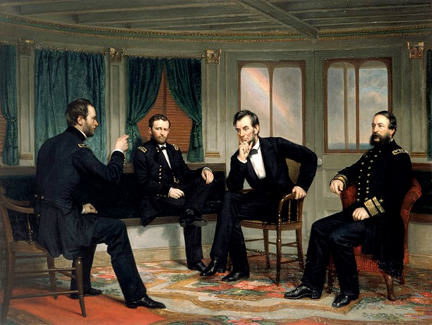

Abraham

Lincoln was not a military man. He had not led men into battle or been trained

at West Point. He had trouble with the generals who first worked under his

command. They dismissed him as a bumpkin who knew nothing of war strategy. He

dismissed them (quite literally) as inept leaders who missed opportunities to

destroy the enemy. When he finally put Ulysses S. Grant in charge of the Army,

he found a general who saw things as he did. Grant waged a brutal war, but he

was effective. Lincoln had always wanted to push deep into the South and cut

off supply lines. He wanted to move mass numbers of troops via rail to the

front lines. In Grant, he found a leader who saw eye to eye with the President

in waging an effective war.

Lincoln

leadership principle #3: If your managers of people don’t believe in you, find

someone else who does.

Never let popularity sway

your standards

It

is hard for those of us on this side of history to believe, but until the Civil

War was being won by the Union troops, Lincoln was very unpopular. There was

some doubt that he would win a second term (he ran against the bungling former

general George McClellan). There were calls for the war to end, especially as

casualties climbed into the hundreds of thousands (over 600,000 deaths – the

most American deaths in any war.) People were sick of it. They were ready to

let the split between North and South remain a permanent divide. Lincoln stuck

to his purpose. He was not willing to stop short of victory.

Lincoln

leadership principle #4: If you let popular opinion shape your values, you will

forever be changing directions. Make sure you are standing on solid values, and

then stand firm.

________

1. Quote is attributed to James

Lane Allen

2. Lincoln’s House Divided Speech was delivered on June 16, 1858 after he had been nominated

to run for the U.S. Senate against Stephen A. Douglas. Lincoln lost to Douglas

in the November election. Two years later, the two were opponents in the race

for the presidency, which Lincoln won.

3. Lincoln’s

Gettysburg Address is one of his most

popular speeches, but almost did not happen. At this point in the war, Lincoln

was so unpopular that the organizers of the dedication of the national cemetery

debated whether he should attend the event. Only because he was the leader of

the nation did they allow him to speak, but only briefly after the keynote

speaker, Edward Everett delivered a two hour speech.